November 27, 2025

Customising for culture – designing sport and entertainment venues for audiences in Asia

Firstly, it’s not just about the requirements of the performer. While that is a primary design consideration to ensure that the space can attract the talent, more attention needs to be paid to the audience and the way people like to interact with and utilise the arena’s surroundings. Cultural differences between Asia and Western nations, and between Asian countries themselves mean that this is often very different to the way audiences in the US or Europe might arrive, behave at, and then leave the venue.

Secondly, we are seeing a significant shift in the types of sports and particularly the types of artists that are being drawn to venues in Southeast Asia and Greater China. The clearest example of this is the rise of K-pop (Korean popular music) in Southeast Asia, which has brought with it a huge market for sport and entertainment tourism across the region in a way that is not common in the West where people are less likely to travel internationally to see their team or favourite singer perform.

Spaces big and small.. and big again

If we look at sports first, often the biggest sports in our region are actually the smallest. We’re not catering for sports like ice hockey here; it’s more focused on sports where the field of play is much smaller such as mixed martial arts, table tennis and badminton. So the way that the venue expands and contracts and how this influences the seating configurations to get closer to the action, as well as where nearby amenities are placed, is very important to consider. If you imagine trying to watch a table tennis match in an arena primarily designed for ice hockey, the audience experience would be terrible. Kai Tak Arena in Hong Kong was designed with this in mind, having a massive 80% of its 10,000 seats retractable or removable to ensure that the venue can be easily and quickly transformed for different sports event.

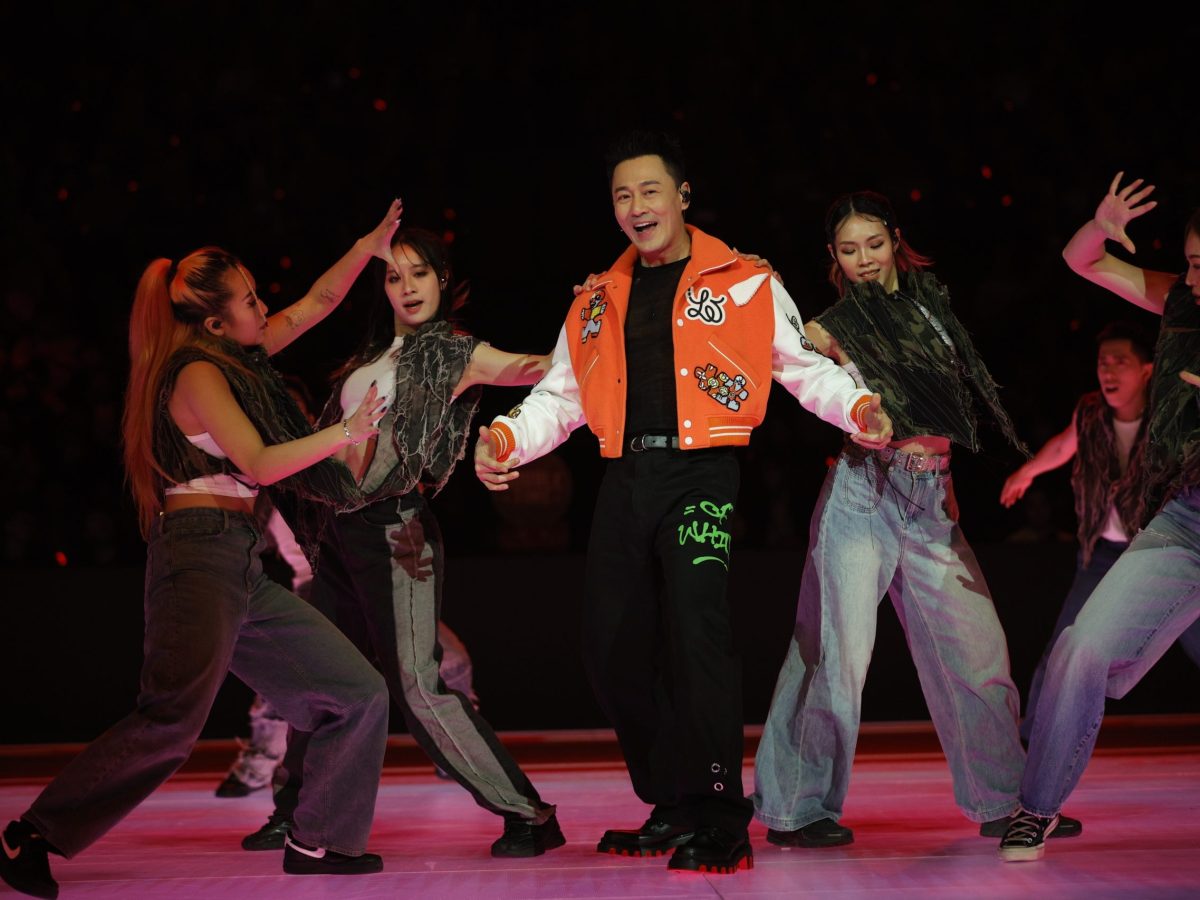

At the same time, we must understand the entertainment context in Asia, particularly the increasing popularity of K-pop artists in the region and the size and scale of their shows. We had Dua Lipa tour Southeast Asia recently with fantastic sold out shows but the rigging and size of staging for the Future Nostalgia tour will be quite different to if an artist like South Korea’s G-Dragon tours. You can imagine that the thrust stage will be wider and longer, there are likely to be satellite stages around the venue and we are seeing more and more that the primary stage is merely the base for the artists who will utilise the full venue space, often coming into the audience on electric vehicles.

Therefore, the spaces you design in Asia must be incredibly flexible to be able to go from big to small and back again, often week to week.

But, as we said earlier, it’s not just about accommodating the needs of different local popular sports and entertainers. Stadia and arenas must also reflect the way local audiences behave when at the venues, and this is often more associated with local culture rather than the performers themselves.

Venues are the cities’ living rooms

What many Asian cities make up for in size, scale and diversity, they also lack in physical space. Apartment living is much more common than in the West, and intergenerational living, sharing of meals, as well as religious traditions, all impact the way people socialize.

An approach to building design, which caters for the different ways people in the region come together, needs to be considered in an arena context. When people step out of their HDB in Singapore, their high rise in Hong Kong or their condo in Bangkok to attend an event, they won’t change the way they culturally interact with their surroundings. The venue needs to adapt to them; not the other way around.

In Japan, the stadia model has long resisted a more traditional mindset that characterises venues as isolated economic assets. Instead, they function as platforms for social cohesion, cultural expression and collective pride. When a neighbourhood sees its identity reflected in new facilities; when teenagers access the same courts as international competitors; when local food and craft traditions integrate with modern programming; then infrastructure becomes genuinely community-based.

If we take food, for example, this is such an important part of culture in Asia. People often eat together and they take their time, enjoying what they have prepared or what has been served. Larger venues in the region tend to sometimes ignore this because it’s too hard to cater for. How can you integrate local culture into the food and beverage offering at an arena when it is often so diverse and not something that can be quickly prepared over a counter? The answer is not simple but it’s something that needs to be explored further, whether it is in the venue or around the precinct. There is an opportunity for famous local culinary brands to find ways to offer their products almost as an appetizer to the main course entertainment at the newer and upgraded venues. At other venues, street food can be elevated to a premium level and offered in the laneways and concourses around the stadia or arena.

Food is commonly eaten in group settings in many parts of Asia so there should also be spaces where this can be done before or after a show. There’s a sense of community in Southeast Asia, for example, where different generations of families live and socialize together. The performance space can be seen as an extension of the home environment. If the hawker centre is the family dining room, then the arena becomes the family living room.

Despite these huge venues being places where thousands gather, they tend to be singular in the way they cater for sports fans or concert goers. You have your own seat number, you go through security individually and you wait in a straight line for your merchandise. It’s counterintuitive that in a place where we want people to come together, we make them feel like they are a number.

Of course, it’s not just about the experience inside the venue; we must remember that unlike some of the largest stadia in the West where people arrive in cars, venues in Asia rely about 95% on public transport to get people to a show. In Southeast Asia and Greater China, there is generally good connection through underground metro rail networks, meaning that what people lose in space, they gain in time to enjoy the trip to the venue as part of the overall experience. This is where the surrounding precinct becomes even more important to ensure it is activated for all the communal and group entertainment reasons we have just discussed.

This is not to say that culture in Asia is homogenous. It’s the diversity that makes designing these large spaces for such different social, religious and community groups so interesting. Whether it is the integration of prayer rooms for those attending a sports event during Ramadan or the inclusion of multi-generational seating so that families can sit together without having older members or those with children separated from the action in their own segregated spaces, venues in Asia have the potential to be the region’s living rooms.

At Kai Tak Sports Park in Hong Kong, the Stadium, Arena and Youth Sports Ground are surrounded by some of the densest housing in the world and the 28 hectare site has become a space where the community gather. The Sports Park is more than just for sports; it is designed to welcome everyone. From one of the city’s largest children’s playgrounds to a visitor gallery, Kai Tak Sports Park is an activated community precinct.

A dining precinct offers a vibrant mix of more than 30 food stalls serving up local Hong Kong favourites, international bites, and artisanal desserts, alongside retail stalls featuring handcrafted goods, lifestyle products, and even pet-friendly treats. With live performances, rotating weekend vendors, and a lively atmosphere, this area of the Park is the ultimate destination for foodies, families, shoppers and pet lovers.

What complicates this diverse and inclusive design intent even further is the success that Asia has had in attracting sport and entertainment tourism. It could be an international table tennis tournament in Malaysia that caters for its many Chinese visitors or Singapore being Taylor Swift’s only tour stop in the region, venues need to be able to adapt to the cultural characteristics and needs of their primary audiences.

Welcoming other cultures onto your home turf

That brings us to the increasing need to recognise visiting cultures while at the same time allowing regional identity to be part of the venue experience. From the wayfinding to the selection of sponsors and advertising, every touchpoint is important to consider in making users feel at home. Or in some cases, not at home.

No other country has such a historical approach to culture in its stadia design than Japan with venues like the New Prince Chichibu Memorial Rugby Stadium sitting within Tokyo’s historic Meiji precinct, where heritage venues including the 99-year-old Meiji Jingu Baseball Stadium continue to operate alongside new developments. Japan has a history of reimagining its ageing sport and entertainment infrastructure for modern use and this infrastructure now serves as a mechanism for regional revival, not just national spectacle. Rather than importing an international design template, Japan examines how tradition and technology can coexist; how sumo wrestling’s 1500-year heritage can share space with modern entertainment; how centuries-old shrines can anchor contemporary mixed-use precincts.

In Hong Kong, Kai Tak Stadium’s South Terrace looks out through a huge glass window onto Victoria Harbour as a window to the city, reminding people where they are. The ‘Pearl of the Orient’ venue as it is affectionately known due to its pearlescent façade that pays homage to Hong Kong’s history also has the Chinese characters “Kai Tak” displayed across its seating, celebrating the rich heritage of the famous district.

Similarly, the new NS Square is not just a performance space; the 30,000 seat venue at Marina Bay in Singapore is set to become a national landmark. Recognising the contributions of national servicemen to the peace and prosperity of Singapore, this arena and community space will be a place for national celebrations and for the community to enjoy. The venue is a gift to national servicemen and their families to show Singapore’s deep appreciation for their work.

The Southeast Asian region, probably more than any other, has seen increased growth, particularly in entertainment tourism, where people will fly one to three hours to a different country to see their favourite performer. Many of these fans don’t want to feel at home. They are in a different country and want to experience and feel those differences. The building itself becomes a destination just like we are seeing, for example with the Sphere in Las Vegas; people want to experience the uniqueness of the venue.

This home venue idea also poses a design challenge in the region when we are designing for multi-team venues. It’s not uncommon for more than one sports team to call a stadium or arena their home venue and while this might seem like a deterrent to creating an identity for the building, if designed to be adaptable to the city, the country and the culture it represents, then the arena creates a sense of belonging for everyone and overcomes any club identity issues – it has its own identity that people get to know and love.

Our challenge and what we enjoy most is designing venues that welcome everyone and are enjoyed by everyone, but which are specific to and functional for their location.

Brett will be speaking on Spaces with Purpose: Creating Landmarks That Anchor Culture and Community at the 2025 Business of Design Week conference in Hong Kong on 3 December while Ismael will discuss the links between culture and technology in the development of sport and entertainment infrastructure at Fortune’s Brainstorm Design event in Macau on 2 December.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur, adipisicing elit. Non facere corporis et expedita sit nam amet aut necessitatibus at dolore enim quis impedit eius libero, harum tempore laboriosam dolor cumque.

Lorem, ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit. Illo temporibus vero veritatis eveniet, placeat dolorem sunt at provident tenetur omnis, dicta exercitationem. Expedita quod aspernatur molestias eum? Totam, incidunt quos.